Brigadier General Francis NASH (1742-1777)

Bird Chronicles

Brigadier General Francis NASH (1742-1777)

page established December 2022 ![]()

Linton Research Fund Inc., Publication © 1987-2023 "Digging for our Roots"

Brigadier General Francis NASH (1740–1777)

3rd great-granduncle Jeff Augustus "Gus" BIRD (1893-1954)

Terry Louis Linton © 2007

Linton Research Fund Inc., Publication © 2007

LINTON & BIRD Chronicles Volume XVII, Issue 4, Winter © 2022, ISSN 1941-3521

Brigadier General Francis NASH (1740–1777) was the 3rd great-granduncle of Jeff Augustus "Gus" BIRD (1893-1954). Frances was the son of Gus’ 3rd great-grandparents Lieutenant Colonel John Hinton NASH (1711–1776) & Anne OWEN (1710–1757)

Parents

Francis NASH (1740–1777) was the son of Lieutenant Colonel John Hinton NASH (1711–1776) & Anne OWEN 1710–1757 emigrants from Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, Wales. John was born on January 1, 1711, in Tenby, Pembrokeshire, Wales, to Elizabeth HINTON, age 22, and Abner NASH, age 26. John’s mother, Elizabeth died in his child birth. [i]

John married Annie in 1733, at the Saint Andrews Church in Hertford, County Hertford, England. They emigrated from Wales to Virginia before 1736. They “settled in Prince George, that part which became Amelia and later Prince Edward County, Virginia, where he bought a large estate in the fork of the Bush and Appomattox Rivers to which he gave the name of 'Templeton Manor.' Here he lived, winning prominence and honor, filling at various times the offices of King's Justice, 1754, High Sheriff, Burgess 1752-1755 and 1756-58; Captain in the French and Indian Wars, and Lieutenant Colonel of the County Militia. Later, he was Chairman of the Committee of Safety for Prince Edward and a member of the convention of 1775. He was Church Warden of St. Patrick's Parish, one of the founders of Hampdon Sydney College, a lawyer and a man of education, dignity and property. [ii] John died on March 8, 1776, at his Templeton Manor, in present day Prince Edward County, Virginia.

John & Anne fifteen known children:

Colonel John Hinton NASH (1729–1802) (3rd great-grandfather of Jeff Augustus "Gus" BIRD 1893-1954); Colonel Thomas NASH (1730–1769); Ann Owen NASH (1730–1795); Mary NASH (1733–1812); Lucy NASH (1736–1817); Brigadier General Francis NASH (1740–1777); Abner NASH (1740–1786) Founder of Nashville Tennessee and Governor of Tennessee; Betty NASH (1741–1776); Elizabeth NASH (1743–1790); Margaret NASH (1744–?); Prissilla NASH (1746–?); Lucy NASH (1748–1810); Ann Francis NASH (1748–1777); Thomas NASH (1754–1854); William NASH (1755–1808)

Early life

Francis was born on May 10, 1740 on his father’s Templeton Manor, Amelia County, Virginia. Francis may have served in the French and Indian War in 1763.

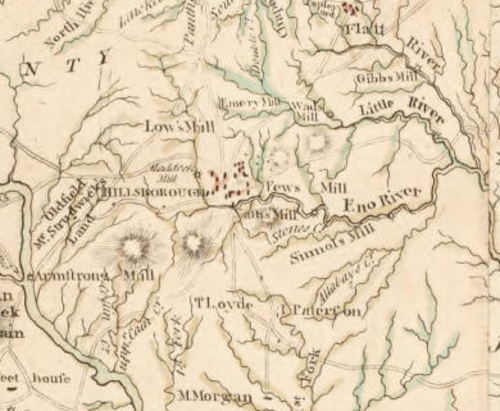

By 1763, Francis had moved along with his brother, Abner to Childsburgh, which later became Hillsborough. There Francis started a law practice and became a clerk of court in 1763, a position which paid an annual stipend of £100 sterling. The Nash brothers also owned substantial property in the town and established a water grist mill on the Eno River, while Francis invested in a local store. From 1764 to 1765, Frances served his first term in the North Carolina Assembly representing Orange County.

Francis was a lawyer, public official and politician in Hillsborough, North Carolina. He involved in opposing the Regulator movement, an uprising of settlers in the North Carolina piedmont between 1765 and 1771. Francis was also involved in North Carolina politics, representing Hillsborough on several occasions in the Colonial North Carolina General Assembly. He became engaged in revolutionary activities and served as a delegate to the first three Patriot Provincial Congresses. In 1775, he was named lieutenant colonel of the 1st North Carolina Regiment under Colonel James Moore, his wife’s grandfather. [iii]

Marriage

Francis married Sarah “Sally” MOORE (1756–1785) in 1764, in Brunswick, North Carolina. Sarah was the daughter of Ensign, later Judge Maurice MOORE (1735–1777) & Ann GRANGER (1729–1804). Sarah was born in 1756, in Brunswick, Newhan County, North Carolina and died on March 6, 1785, at Point Repose Plantation, New Hanover County, North Carolina. Francis & Sarah had two known children; Ann NASH (1771–1784) and Sarah NASH (1773–1837) both born in Hillsborough, Orange County, North Carolina. Sarah lost her husband to the cause of freedom during the Revolutionary War and became a young widow, with 2 small children to raise. [iv]

Death & Legacy

Brigadier General Nash was the commander of the First North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army, at the Battle of Germantown, Kulpsville, Pennsylvania. On October 4, 1777, he was mortally wounded by a cannonball that struck him in the hip and killed his horse during the battle. He died three days later on October 7, 1777. He was buried in the nearby Towamencin Mennonite Churchyard, Kulpsville, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. [v]

The following were named in his honor: Fort Nashborough, in Nashville, the cities of Nashville, Tennessee, Nashville, North Carolina, Nashville, Georgia, Nash County, North Carolina, General Nash Elementary School in Towamencin Township, Pennsylvania, and the USS Nashville (LPD-13) (Amphibious Transport Dock), Francis Nash Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).

Revolutionary War 1775 to 1783

Letter to Sally Nash from Francis Nash, dated July 25, 1777

"Is it possible, with such an army and a Washington at their head, that Americans have anything to fear? No, my dear Sally; I now feel the fullest assurance that can be founded on human events that nothing less than the immediate interposition of Providence (which I will not suppose to be excited in favor of tyranny and oppression) can prevent us from the invaluable blessings of liberty, freedom and independence. With those assurances I rest satisfied, with the blessing of Heaven, of returning to you erelong crowned with victory, to spend in peace and domestic happiness the remainder of a life which, without you, would not be worth possessing."

Sources

[i] England & Wales, Christening Index, 1530-1980: Genealogical Society of Utah. British Isles Vital Records Index, 2nd Edition/i. Salt Lake City, Utah: Intellectual Reserve, copyright 2002. Used by permission.; Publisher, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2008, Provo, UT, USA; Repository Ancestry.com …. American Genealogical-Biographical Index (AGBI); Record details, Name John Nash, Birth Date 1710-1719, Birth Place Virginia, USA; Volume 123; Page number 290; Reference Kith & Kin of Capt. James Leeper & Susan Drake His Wife. By Nellie Lousie McNish Gambill. [New York?] 1946. (196p.) :11

[ii] Notes for John Nash: From "The Reads and Their Relations," by Alice Read (Mrs. Shelly Rouse), Published 1930, contained in Virginia State Library.

[iii] Nash, Francis (1903). Hillsboro, Colonial and Revolutionary. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton. OCLC 6407838. …. Abstract of Graves of Revolutionary Patriots; Volume: 3; Serial: 11670; Volume: 3; Author, Hatcher, Patricia Law; Publisher, Online publication - Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999.Original data - Hatcher, Patricia Law. Abstract of Graves of Revolutionary Patriots. Dallas, TX, USA: Pioneer Heritage Press, 1987.Original data: Hatcher, Patricia Law. Abstract of Grave; Repository Ancestry.com Address http://www.Ancestry.com

[iv] Nash, Francis ("Frank") (1906). "Francis Nash". In Ashe, Samuel A'Court (ed.). Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present. Vol. 3. Greensboro, NC: C.L. Van Noppen. OCLC 4243114.…. American Genealogical-Biographical Index (AGBI); Godfrey Memorial Library; Middletown, Connecticut; American Genealogical Biographical Index; Volume Number: 120; Author Godfrey Memorial Library, comp; Publisher, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 1999, Provo, UT, USA; Repository Ancestry.com Address http://www.Ancestry.com

[v] Siry, Steven E. (2012). Liberty's Fallen Generals: Leadership and Sacrifice in the American War of Independence. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59797-792-0.

Francis Nash's home in Hillsborough, now known as the Nash-Hooper House

A portion of John Collet's 1770 map of North Carolina depicting the environs of Hillsborough and the Haw and Eno Rivers

Francis Nash

Meet the Ancestors

My Revolutionary forebears put the “Nash” in Nashville

by Hugh O. Nash Jr., BE’67

Southern Journal — Summer 2008

Vanderbilt School of Engineering

Reprint by Linton Research Fund Inc., Publication © 2022

In 1962 my decision to apply to Vanderbilt School of Engineering made little or no sense. I had grown up in Savannah, Ga., and knew little about Vanderbilt and even less about Nashville–except that the city was named for my ancestor Francis Nash.

When I informed my high school guidance counselor of my college choice, I was told that I should not aim so high. That did it. I applied, and against all odds, Vanderbilt, my singular choice, accepted me for early admission.

Alexander Heard had just been named Vanderbilt’s chancellor. My mother had dated him as a high school student in Savannah, and she assured me that if I ever landed in jail, “Alex” would get me out.

Despite my excellent prep-school training, I took a beating in Melvyn New’s freshman English class. Words like “trite,” “redundant,” “clichéd,” “hackneyed” and “verbose” continued to appear in red pencil on my English compositions. I was, however, permitted to opt out of Western Civilization–discretion being the better part of valor (another cliché).

Upon my Vanderbilt graduation in 1966, I returned to Savannah and worked there for eight years before moving my family to Nashville, where I had accepted an engineering position. Back in Nashville my interest in Francis Nash and his older brother, North Carolina Gov. Abner Nash (my fourth great-grandfather), led to what would become my all-consuming passion: the American Revolutionary period.

As my interest grew, I became acutely aware that the American Revolution is a forgotten war, particularly in the South where it is overshadowed by the War Between the States. Few of this generation can name a single Revolutionary War general other than George Washington and perhaps Lafayette.

Periodically, I would write an article for The Tennessean about Brig. Gen. Nash, who gave his life for his country and his name to Nashville. In 2001 the Francis Nash Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) asked me to address its members on the occasion of its 70th anniversary.

Rather than filing away my talk afterwards, I kept writing. The Tennessee State Archives provided much information about the North Carolina history of the two Nash brothers, and the Library of Congress and the University of Virginia provided online transcriptions of letters that proved invaluable–letters to (and from) Abner and Francis Nash, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and members of the Continental Congress. My book, Patriot Sons, Patriot Brothers (2006, Westview Publishing Inc.), places the lives of Francis and Abner Nash in the historical context of the defense of Philadelphia, the Southern campaign of the American Revolution, the Continental Congresses, the drafting of the North Carolina and U.S. constitutions, the settling of East and Middle Tennessee, and the naming of Nashville, Tenn.

History makes no record of either brother ever visiting the area that would become Middle Tennessee. How, then, did Tennessee’s capital city come to be called Nashville?

My fifth great-grandfather, John Nash, owned a 13,000-acre tobacco plantation in Prince Edward County, Va. His sons, Francis and Abner, sold their inheritance to seek their fortune. Francis relocated to Hillsborough, N.C., in 1763. The two brothers dammed the Eno River, built a grist mill, and invested in several other Hillsborough businesses. Abner moved on to New Bern, where he would become perhaps the best trial attorney in the Province of North Carolina.

Francis was appointed superior court judge at the age of 21. As Hillsborough grew to become the political and cultural center of the province, Francis grew in stature and popularity. Francis married Sarah (Sally) Moore, granddaughter of the colonial governor of South Carolina.

Francis Nash was handsome and athletic and presented a striking image on horseback, according to William Richardson Davie, lawyer, soldier, and founder of the University of North Carolina. History indicates that Francis’ appearance did not go unnoticed by the local barmaids.

As members of North Carolina’s ruling class, with the advantages of birth, wealth, education and marriage, Francis Nash and his brother, Abner, served in the colonial assemblies of Royal Governors William Tryon and Josiah Martin.

In 1771, serving under Gov. Tryon, Francis Nash proved himself courageous in the Battle of Alamance, fighting a band of “regulators”–backcountry farmers who had organized an armed rebellion to protest abuse by the provincial government. Alamance would forever change Francis Nash’s worldview. The king’s governor hanged one of the rebels, James Few, near the battlefield and executed several more regulators in Hillsborough–all without trial.

Over the next five years, Francis Nash attended the not-so-clandestine provincial congresses, where grievances against King George III were debated. When North Carolina signed the Declaration of Independence, Nash was appointed colonel in North Carolina’s Continental Army and later became brigadier general.

After the defense of Charleston in 1776, Nash returned to North Carolina to recruit. He marched his nine regiments, consisting of 2,000 men, north to join George Washington, arriving in Philadelphia in time to attend the first Fourth of July celebration.

Nash served at the Battle of Brandywine Creek and then at Germantown, both in the defense of Philadelphia. At Germantown, as Francis marched his troops behind Washington’s caravan, a 6-pound cannonball flew out of the smoke and fog and over Washington’s head. The ball struck Nash’s horse in the neck and crushed Nash’s thigh. Both fell to the ground, with the brigadier general pinned under the dead horse. Maj. James Witherspoon was killed instantly when the same ball struck him in the head.

George Washington assigned his personal physician to care for Nash, but the general could not be saved. After enduring a bumpy and painful 30-mile wagon ride, Nash died four days later at nearby Towamencin on the road to Valley Forge. He is said to have bled through two feather beds.

Nash’s funeral was attended by American Revolutionary War heroes Washington, Lafayette and Pulaski; Generals Nathanael Greene, Anthony Wayne and John Sullivan; and 11,000 continental soldiers. Francis Nash left behind a wife and two young daughters. What a terrible price this 35-year-old officer paid for our country.

Abner’s slight physique and poor health made him unfit for battle, but he demonstrated no less love for his country than his brother. One contemporary described him as “vehemence and fire” in the courtroom. While Francis Nash fought the king’s army, Abner was serving as the first speaker of North Carolina’s House of Commons.

Following his brother’s death, Abner Nash was elected North Carolina speaker of the senate, and then governor. He was inaugurated governor the very day Charleston fell to the British. His term spanned the debacle at Camden and the successful battles of Kings Mountain, Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse.

In the fall of 1786, Abner, who had endured the ravages of tuberculosis for most of his public life, traveled to New York to represent North Carolina in the Congress. His consumption worsened.

“Congress has not yet elected a President owing to their [sic] being too few States on the floor,” wrote Virginia Congressman William Grayson to James Monroe on Nov. 22. “Mr. Nash of N. Carolina, who lies dangerously ill, is talked of generally, & nothing but his death or extreme ill health I am persuaded will prevent his election [as president of Congress].”

Abner Nash, age 46, died a few days later. Had he lived, he likely would have become president of the Congress, and no doubt would have signed the United States Constitution for North Carolina nine months later.

Tennessee did not become a state until 1796. While Francis Nash was fighting the British and Abner was helping establish a fledgling new government, Daniel Boone was exploring the vast lands to the west. Boone convinced North Carolina judge Richard Henderson that the time was right for western investment, and in 1775 Henderson and several others, including North Carolinian James Robertson, struck a bargain with the Cherokee Indians. For 2,000 pounds sterling and another 8,000 pounds in goods, the Cherokees deeded over more than 20 million acres, which included about two-thirds of present-day Kentucky and much of Middle Tennessee.

Francis Nash had served in Henderson’s court, and two others investors, Thomas Hart and William Johnston, had been associates of Nash in Hillsborough. It is likely that Thomas Hart’s brother and partner, Nathaniel Hart, knew Francis as well. The State Record of North Carolina in 1784 recorded an act calling for the establishment of a town to be called “Nash-Ville, in memory of the patriotic and brave General Nash,” on the Cumberland River near the French Lick.

Two other towns also would come to be named for Francis Nash: Nashville, Ga., and Nashville, N.C.

Francis Nash’s final resting place, however, is at Kulpsville, Pa., a few miles from the place where a cannonball felled him. Many years later, in 1935, Nashville, Tenn., experienced what must have been a media frenzy when a movement to remove Gen. Nash’s body to the city named in his honor caught fire. The Daughters of the American Revolution got involved. There were letters to the editor, telegrams, and even a special telephone exchange set up by Southern Bell to receive votes in favor of the proposed removal. But the body was never moved.

Today Francis Nash’s grave remains in Pennsylvania, where he fought his last battle. The only marker commemorating him in Nashville, Tenn., is a bronze plaque downtown at the Fort Nashborough facsimile on First Avenue.

My ancestor never could have predicted that he would lend his name not only to a city he had never visited, but to an enduring style of music. Nashville’s phone book lists more than 50 households of Nashes. Most, I suspect, do not trace their names back to my ancestors and know little of the man for whom their city is named.

North Carolina State Highway Marker photo by Lesley Looper

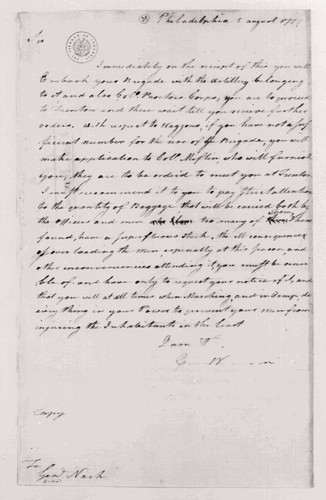

Written Order from General George Washington in Philadelphia to Brigadier General Francis Nash to embark his Brigade and artillery at the receipt of this to Trenton, New Jersey to await Furter orders. (This is a work-in-progress will try and put the full contents on website)

Francis NASH (1742—October 7, 1777)

Biograph

Wikipedia Free Encyclopedia

Linton Research Fund Inc., contributor

Francis NASH (1742—October 7, 1777) was a brigadier general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Prior to the war, he was a lawyer, public official, and politician in Hillsborough, North Carolina, and was heavily involved in opposing the Regulator movement, an uprising of settlers in the North Carolina piedmont between 1765 and 1771. Nash was also involved in North Carolina politics, representing Hillsborough on several occasions in the colonial North Carolina General Assembly.

Nash quickly became engaged in revolutionary activities, and served as a delegate to the first three Patriot provincial congresses. In 1775, he was named lieutenant colonel of the 1st North Carolina Regiment under Colonel James Moore, and served briefly in the southern theater of the Revolutionary War before being ordered north. Nash was made a brigadier general in 1777 upon Moore's death, and given command of the North Carolina brigade of the Continental Army under General George Washington. He led North Carolina's soldiers in the Philadelphia campaign, but was wounded at the Battle of Germantown on October 4, 1777, and died several days later. Nash was one of only ten Patriot generals to die from wounds received in combat between 1775 and 1781.[1] He is honored by several city and county names, including those of Nashville, Tennessee, Nashville, North Carolina, and Nash County, North Carolina.

Francis Nash's home in Hillsborough, now known as the Nash-Hooper House

Nash was born around 1742 in Amelia County, Virginia[2] (in an area that would later become Prince Edward County) to John and Ann Owen Nash. His parents were originally from Wales, and several of his seven siblings,[2] including at least one brother,[3] were born there. One of Nash's brothers was Abner Nash, who later became a statesman in North Carolina.[4]

By 1763, Francis Nash had moved along with Abner[5] to Childsburgh, which later became Hillsborough. There Francis started a law practice, and became a clerk of court in 1763,[4] a position which paid an annual stipend of £100 sterling.[6] The Nash brothers also owned substantial property in the town, and established a mill on the Eno River,[5] while Francis invested in a local store.[7] From 1764 to 1765, he served his first term in the North Carolina Assembly representing Orange County.[4]

In 1770, Nash married Sarah Moore, the daughter of colonial jurist Maurice Moore, niece of James Moore, and sister of future United States Supreme Court Alfred Moore.[8] Their union would produce two daughters:[4] Ann, who died as a child, and Sarah, who went on to marry John Waddell, the son of North Carolina colonial soldier Hugh Waddell,[9] and was the grandmother to American Civil War Confederate blockade runner James Iredell Waddell.[10] Nash had two children out of wedlock, one of whom some scholars identify as a son also named Francis Nash, possibly born in 1770 or 1771.[4] The mother of one of the children was reported as Hillsborough barmaid Ruth Jackson.[11][12][13] The elder Nash provided Jackson with property west of Hillsborough, and several slaves.[13]

War of the Regulation and pre-Revolution politics

Nash showed an interest in military affairs while living in Hillsborough, and received informal military training from a retired English soldier living there. He worked his way up through the Orange County militia ranks until he eventually became its commanding colonel.[14] During the War of the Regulation, in 1768, he ordered the militia to put down several riots incited by the Regulators, but the militiamen were sympathetic towards the rioters and refused.[15] Nash entered into a pact with others including Edmund Fanning, Adlai Osborne, and future governor Alexander Martin, to protect one another's property against Regulator threats, but the parties to that agreement lived at great distances from each other, rendering the pact ineffective.[16]

Along with Fanning, who was a personal friend,[5] Nash was accused of extorting money from Hillsborough's residents. Regulator leaders attempted to have Nash tried for corruption, but the charges against him were dismissed.[4][17] In September 1770, a group of Regulators took control of Hillsborough, forcing Nash and other public officials to flee for fear of bodily harm.[18] Nash subsequently fought alongside Governor William Tryon in the Battle of Alamance against the Regulator militia. He served in the "Lower House" of the colonial Assembly in 1771 and from 1773 to 1775 as a representative for Hillsborough.[4]

In 1774, Royal Governor Josiah Martin postponed the scheduled convening of the colonial Assembly to prevent the North Carolina Assembly from selecting delegates to the proposed Continental Congress, which was to begin in Philadelphia in September. In response, members of the Assembly, many of whom would later become Patriot supporters, convened the First North Carolina Provincial Congress in August 1774. Nash and his brother, Abner, were both elected to that body, along with 69 other North Carolinians, which then selected delegates to the Continental Congress.[19] Governor Martin condemned the Provincial Congress as an extra-legal body not permitted to assemble and represent the people of North Carolina.[20] In an attempt to quash its work, the Governor called the colonial Assembly to convene on April 5, 1775, but the Second North Carolina Provincial Congress met in a session several hours before the Assembly was set to open and many of the congressional delegates, including Nash, voted to support the work of the Continental and Provincial Congresses. In response, Martin dissolved the Assembly. The Royal government would never again call an Assembly to session in North Carolina.[21]

American Revolutionary War

Southern theater

In 1775, Nash served in the Third North Carolina Provincial Congress, which organized eight regiments of soldiers on instructions from the Continental Congress. Later that year, the Provincial Congress appointed Nash lieutenant colonel of the 1st North Carolina Regiment under the command of then-colonel James Moore. In November, the 1st North Carolina was formally integrated into the Continental Army organization. Nash served as an officer under Moore during the maneuvers that led up to the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge in February 1776 but, like Moore, did not participate in the battle, arriving after its conclusion.[22]

During April 1776, Nash was promoted to colonel to replace Moore, who had been promoted to brigadier general.[23] Nash took part in the expedition to aid Charleston in 1776, which culminated in the Battle of Sullivan's Island.[4] Immediately prior to that engagement, Nash had been ordered by Major General Charles Lee, commander of the Southern Department, to relieve William Moultrie's South Carolina troops on Sullivan's Island, but the British assault prevented that relief. Moultrie would go on to successfully defend the island from a much larger British force,[24] while Nash's unit guarded the unfinished rear of Fort Sullivan.[22]

Philadelphia campaign

Nash returned with his regiment to North Carolina in anticipation of joining General George Washington's army in the north, but fears of British and Indian attacks in Georgia prevented any such action, and caused Nash to remain in his home state. On February 5, 1777, he was promoted to brigadier general by the Continental Congress.[4] He was also tasked with recruiting more soldiers from the western part of the state, but was forced to abandon that task after James Moore's death on April 15, 1777. Nash was then placed in command of the North Carolina brigade. Although fellow North Carolinian Robert Howe's commission as a brigadier general predated Nash's, Howe had been made commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army, and he was forced to remain in command of the troops defending South Carolina.[25][26] Nash marched north to join Washington's army and commanded all nine North Carolina Continental Army regiments at the Battle of Brandywine.[4]

Battle of Germantown and death

After the British captured Philadelphia on September 11, 1777, Washington took to the offensive and struck at the main part of the British Army near Philadelphia in the Battle of Germantown. Initially, the North Carolina brigade was intended to serve in the Continental Army's reserve but Washington, out of a desire to defend his flank, ordered Nash into action.[27] Nash was commanding a fighting retreat, slowly moving his unit backwards to stall the British advance, when, on October 4, 1777, he was mortally wounded by a cannonball that struck him in the hip and killed his horse . The same cannonball killed Major James Witherspoon, son of John Witherspoon, the president of Princeton University and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.[28] Nash may have also been blinded by a musket ball that struck him in the head. Thomas Paine, who saw him taken off the battlefield, later stated that Nash's wounds had made him unrecognizable.[29]

Nash was treated by Washington's personal physician, James Craik, who could not stem his bleeding, which was reported to have fully soaked through two mattresses.[28] Nash succumbed to his wounds on October 7 at a private residence near Kulpsville, Pennsylvania. His final words are alleged to have been "From the first dawn of the Revolution I have been ever on the side of liberty and my country".[30] He was buried in the Towamencin Mennonite Meetinghouse Cemetery in Towamencin Township, Pennsylvania, on October 9, 1777, along with other officers who had perished at Germantown.[4] Most of the Continental Army's senior officers, including Washington himself, attended the funeral service.[31] Nash's friend and colleague, Alexander Martin, who later became Governor of the State of North Carolina and who had witnessed Nash's wounding, subsequently composed a funeral poem in the fallen general's honor.[32]

Legacy

Highway Historical Marker near Nash's home in Hillsborough, North Carolina

Nash was one of only ten Patriot generals who died during the American Revolutionary War.[1] After his death, on April 29, 1784, Congress awarded his heirs a land grant representing 84 months of Continental Army service, which exceeded Nash's actual service time.[33] Nashville, Tennessee (originally called "Fort Nashborough"),[34] Nashville, North Carolina,[35] and Nash County, North Carolina,[36] are named in his honor. In 1906, a stone arch was erected on the grounds of Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in Nash's honor, but it was demolished in 1937.[37] Nash's home in Hillsborough is now known as the Nash-Hooper House, as it was purchased by William Hooper, a signatory to the Declaration of Independence, after Nash's death. In 1938, a historical marker was placed near the house commemorating Nash's life and service.[34] The Nash-Hooper House was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1971.[38][39][40] It is located in the Hillsborough Historic District.

References Notes

Davis 1981, p. 4.

^ a b c d e f g h i j k Reed 1991, p. 358.

^ a b c Davis 1981, p. 5.

^ Davis 1981, p. 7.

^ Waddell 1885, p. 200.

^ Davis 1981, p. 8.

^ Davis 1981, p. 9, stating that the child with Ruth Jackson was a daughter

Nash 1906, p. 296.

^ Lefler & Powell 1973, p. 266.

^ Rankin 1971, p. 62.

^ Rankin 1971, pp. 74–75.

^ Rankin 1971, pp. 88–89.

^ Bennett & Lennon 1991, p. 51.

^ Rankin 1971, p. 113.

^ Rankin 1971, p. 115.

^ Rodenbough 2010, pp. 51–52, 174.

^ Babits & Howard 2004, p. 193.

^ : a b "Marker: G-10 – FRANCIS NASH". North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

^ "The Town of Nashville, North Carolina". Town of Nashville. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

^ "History of Nash County". Nash County, NC – Official Website. Nash County. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

^ "Francis Nash Arch (Removed), Guilford Courthouse". Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, Documenting the American South. University of North Carolina Libraries. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

^ "Nash-Hooper House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

^ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

^ Charles W. Snell (March 27, 1971). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Nash-Hooper House (William Hooper House)" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying two photos, exterior, from 1969 and 1971 PDF (32 KB)

Bibliography

Babits, Lawrence; Howard, Joshua B. (2004). "Fortitude and Forbearance": The North Carolina Continental Line in the Revolutionary War 1775–1783. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Archives and History. ISBN 0-86526-317-5.

Bennett, Charles E.; Lennon, Donald R. (1991). A Quest for Glory: Major General Robert Howe and the American Revolution. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1982-1.

Davis, Louise Littleton (1981). Nashville Tales. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-88289-294-8.

Kars, Marjoleine (2002). Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator Rebellion in Pre-Revolutionary North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4999-6.

Lefler, Hugh T.; Powell, William S. (1973). Colonial North Carolina: A History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-13536-1.

Nash, Francis (1903). Hillsboro, Colonial and Revolutionary. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton. OCLC 6407838.

Nash, Francis ("Frank") (1906). "Francis Nash". In Ashe, Samuel A ‘Court. Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present. Volume 3. Greensboro, NC: C.L. Van Noppen. OCLC 4243114.

Rankin, Hugh F. (1971). The North Carolina Continentals (2005 ed.). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1154-2.

Reed, John F. (1991). "Nash, Francis". In Powell, William S. Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Volume 4 (L–O). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1918-0.

Rodenbough, Charles D. (2010). Governor Alexander Martin: Biography of a North Carolina Revolutionary War Statesman. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1684-4.

Siry, Steven E. (2012). Liberty's Fallen Generals: Leadership and Sacrifice in the American War of Independence. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59797-792-0.

Waddell, Alfred (1885). A Colonial Officer and His Times, 1754–1773: A Biographical Sketch of Hugh Waddell. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Co. OCLC 16153240.

External links

Photographs of grave monuments of Nash

Monument to Brigadier General Francis Nash ((17401777) at the Towamencin Mennonite Churchyard, Towamencin Mennonite Meetinghouse Cemetery, Towamencin Township, Pennsylvania, On this spot burial services were held October 9, 1777 for Gen Nash, Col Boyd, Maj White and Lieut Smith. Erected by the people of the community.

Linton Research Fund Inc., Publication © 1987-2024 "Digging for our Roots"

Main Menu

Linton Research Fund, Inc., HOME PAGE

LINTON Chronicles Table of Contexts

LINTON Ancestors in the Revolutionary

LINTON Ancestors in the Civil War 1861-1865

BIRD Chronicles Table of Contents

Bird Ancestors in the Revolutionary War

BIRD Ancestors in the Civil War 1861-1865

Today's Birthdays & Anniversaries

History of the Linton Research Fund Inc., LINTON & BIRD Chronicles

LINTON & BIRD Chronicles on Facebook

![]() "Thanks for Visiting, come back when you can stay longer" Terry Louis Linton © 2007

"Thanks for Visiting, come back when you can stay longer" Terry Louis Linton © 2007

Linton Research Fund Inc., Publication © 1987-2024 “Digging for our roots”

LINTON & BIRD Chronicles

Established 1984

Quarterly Publication of the Linton Research Fund Inc. ![]()

_historical_marker_500x373.jpg)